Featured

Gibson Exclusives

Collections

By Body Style

Gibson Exclusives

Collections

Gibson Amplifiers

MESA/Boogie Amplifiers

Cases

Guitar Accessories

Apparel

Lifestyle Accessories

WELCOME

Maintenance & Service

![image System.Collections.Generic.Dictionary`2[System.String,System.String]](png/gibson_electric_certified_vintage_image_200x165.png)

![image System.Collections.Generic.Dictionary`2[System.String,System.String]](png/gibson_tv_the_process_flyout_200x165.png)

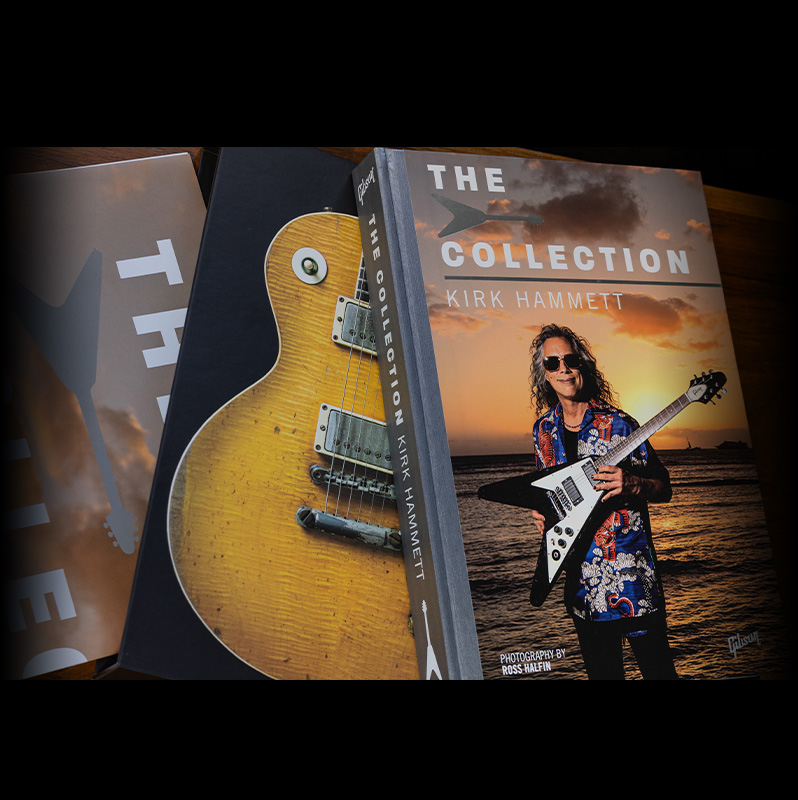

![image System.Collections.Generic.Dictionary`2[System.String,System.String]](png/the_collection_title_card_flyout.png)